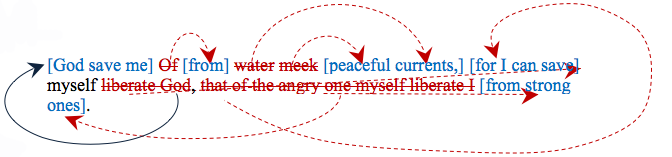

De Agua Mansa Me Libre Dios, Que De La Brava Me Libro Yo

Lina Ferreira Cabeza-Vanegas

DE AGUA MANSA ME LIBRE DIOS, QUE DE LA BRAVA ME LIBRO YO

or

Of water meek myself liberate god, that of the angry one myself liberate I.

or

or

God keep me from still waters.

or

“They run deep.”

or

The cacique loved his wife very much; he even told her so, often, in fact—at least in the beginning. How he’d seen her in a crowd of her kin and wanted her immediately—from marrow to skin, wanted her, wholly and whole. He’d run a finger from her neck to her navel, slowly zigzagging between clavicles, breasts and ribs, and he’d tell her about that day as if she hadn’t been there. As if she didn’t know there had been red-terracotta snakes painted on her skin, cascading down the sides of her face, arching their backs against her cheek bones and braiding themselves into long geometric columns down her arms and legs. As if she didn’t know the contour of her own face and breasts and hips, he’d run his finger down on her skin as if he were explaining directions on a map, “From here to here, and here to there, turn at hip bone, pause at scar, straight down and in.” And he’d tell her again and again, how when he’d seen her eyes and heard her laugh she’d made the snakes come to life. How, though no one else had seen it—not even her—he had. He’d seen her and seen them sliding down her thighs, around her ankles and between her toes, across the dirt and right into the cacique’s bones. “I saw you looking at me and I felt them crawling up, and that was that,” and he’d land his hand on her hip and push her against a wall, against the ground, against the sharp edge of a rock. He’d press his hand and then his body, like the snakes were clamoring inside him to come back to her, leap from him back into her, a terracotta tangle, snakes and flesh.

And it wasn’t bad. She put her hand over his and leaned back when he pushed. She untangled his hair and gently removed the gold breast plate, bracelets and rings when he fell asleep drunk and crying on her lap, she blushed when he toasted her at his banquets, and she attended every banquet. One after the other, after the other, after the other. Until one day he ran his finger down her sternum, down the valley where ribs meet and noticed a belly suddenly swelling.

She wrapped her arms around taut belly skin and listened to him as he told her again, how he’d wanted her first and last and immediately, how much still, how much forever. She’d listened while he drank and cried and fell asleep on her lap, saying, “All I’ve ever wanted, all and everything and nothing else, ever-ever, I promise.” And then a child was born. A little girl like a hummingbird, so light when she was born if he closed his eyes he wasn’t sure he was holding anything at all, and so fast when she became a girl at times she seemed to almost be standing perfectly still. And that was enough for a while, a while and a half, until it wasn’t anymore and he arched his back and said, “A nice little banquet, I think, nothing too big.”

Nothing too big, then something slightly big, then something so big so often that the nights became one endless blur of music, fire and faces. She tried to go once or twice, when their daughter was still very little and needed to be held, but these things are loud and bright and she had to leave before things even really got started. If she’d tried again perhaps she might have noticed the cacique slipping out with one or two women every so often, maybe she’d have caught his eye as he came back dusting his shoulders and pulling sticky seeds from his hair. But she didn’t need to see him slipping out, it was enough that he never came back to her at night, or even for days and weeks, a month once, at least.

By the time she could rejoin the cacique’s elaborate banquets he didn’t so much as go through the theatricalities of guilt. No effort put into slinking or whispering, no telling this girl or that woman to wait by that tree or this wall, nothing. Five times, the cacique’s wife made note, he’d outright tossed a woman like a fresh deer carcass over his shoulder and carried her out. And once, he’d completely covered his body in gold dust and made the particularly beautiful wife of a noble man lick him clean before all in attendance, after which he’d taken the habit of carrying a pouch of gold dust around his neck, just in case. He came and went from banquet to bed, he stumbled home only ever accidentally and he did not see his wife drawing red terracotta snakes in more and more elaborate knots and braids, down her arms, and legs, and between her toes, and he did not see the shaved-head güecha warrior seeing what he didn’t.

That’s where the story begins. Seeing, not seeing, and forgetting having ever seen at all. That’s where it begins and ends. Because after being seen so intensely for so long the cacique’s wife couldn’t go without it and she had to meet her lover often. She had to run her finger down his chest, tell him about the night they’d met and bite the tip of his fingers to watch him drown a scream in his throat for fear of being discovered. It’s not the same for men and women, the burden is different and the cacique cannot allow certain things to be whispered or rumored. He must take note and precautions, he must invite his wife to one more banquet and make himself perfectly clear, there is no other way around it. He must be clear publicly about present and future things, so that everyone understands that she must be made to understand, that even though it may be hard for her to see right then she must come to see that he has no choice but to serve her her lover’s penis on a plate before bringing out what’s left of the warrior tied to a pole—a grunting dripping mess of blind flesh spitting chunks of a ripped out tongue before a priest finishes the deed by ripping out his heart and setting it next to his penis on the plate, the true culprits side by side on a plate of gold before the cacica of Guatavita. And she must be made to eat them, to set things right and put them away, where no one can see.

The cacique’s wife could neither turn from the sight nor keep her stomach from turning. She fell to the ground shaking and weeping and vomiting while the braver part of the court congratulated the cacique and pretended away their repulsion, though it took everything in them to do so. The sight and smell were so overpowering most didn’t notice the cacique’s wife running and pushing her way out of the crowd. By the time they noticed she was holding her sleeping daughter tightly and running through the fog like she’d practice the route in her mind a million times. This is how most things begin; an inconsolable woman holds her child and runs into a lake.

The water was cold and the little girl woke up, but the fog was thick and her mother was crying so she didn’t say a word. She remained limp but wide eyed in her mother’s arms staring back at her father while he yelled for the cacica to come back to shore, to leave his daughter, to come back, to not take the child at least, please, please. But the cacique’s wife did not turn back. Not when her husband begged, not when the cacique commanded, not even when he sent his holiest priests and mohánes in after her.

She was gone, they told him, no way around it. The holiest mohán even swam all the way to the bottom and came back. Dripping in his white robes he told the cacique, “She sits in a throne in the midst of live wreaths of blue and green snakes. She won’t come back now, not now.” But the cacique couldn’t bear it, he kept begging and pleading and screaming to bring back, at least, his little hummingbird child, who drummed her fingers on his cheeks like beating wings to wake him up. So the mohán stood up again and shaking his head went back into the water.

With nothing left to do the cacique sat perfectly still by the lake, not crying, not sleeping, not blinking at all. He stared at the water, at his breath condensing in the air, and the little flat stones his wife had overturned on her final sprint. He sat, crossed legged and stared, paralyzed by a sudden hyper awareness of himself. The dimensions of his feet, the length of his hair, the beating of his heart, “oh heart, the heart,” he heard himself say before he could really form the words in his mind. Then it was the weight of his head, the width of his fingers and the coiling of his intestines; the noises of a thing alive, ticking, pumping, rushing, blinking, growing, stirring, and curdling. He saw himself seeing himself, heard himself hearing, a heartbeat beating in concentric echoes, a man noticing himself noticing his noticing and he felt with distinct acuteness the half-digested banquet meat climbing up his esophagus, splashing against his teeth and foaming out the sides of his mouth. Still paralyzed he vomited on his own lap and let the rest drip down his chin. He sat and waited, hearing and seeing and seeing himself hearing and seeing everything around him until he was sick and dizzy and twice as paralyzed as before, then the mohán emerged with a shivering child in his arms.

"A little dragon,” the mohán began to say and the cacique tried to lift himself from the ground. “See, you have to close your eyes,” he started again, “when you swim to the water realm,” and again the cacique tried to move but nothing budged. His eyes darted back and forth, like children trying to tip a boat, but nothing, nothing. “You have to; we all know that but how could she?” The mohán seem too distracted to notice the cacique’s struggle and simply brought him the child so he could see the empty sockets where something had nibbled away her eyes. “Little dragons do it, I’ve felt them before.” Now the cacique heard nothing, felt nothing, saw nothing but his daughter’s face. “They’ve little mouths and rows of frail teeth, and can’t get a good bite of anything harder than an eyeball,” the hyperawareness, having completely devoured and choked on itself, left little behind. “That’s why you have to, always. But she wouldn’t have known that.” Only the world through a pinprick hole and on the other side a little girl, pink water pooling inside empty sockets, and the realization of all that had come before this moment to make it this specific moment and no other. Then the cacique was finally able to move. He held the little girl’s hand—little bones, wet skin, soft tips—he brushed her hair back, dipped his finger into the gold-dust pouch and drawing snakes on her face told the mohán to take her back to her mother and take care to close his eyes on the way down.

Lina Maria Ferreira Cabeza-Vanegas graduated from BYU with a BA in English and is concurrently completing two MFA's at the University of Iowa in Creative Nonfiction and Literary Translation. She was born and raised in Bogota Colombia, translates from Spanish to English and is interested in untranslatable and linguistically unnegotiable.